From Hollers to Soul Music: How Sinners Contextualizes Black Music History

breaking news: blues obsessed black woman enjoys movie about blues and black people

Seems like every person I know was hitting my line during Sinners’ opening week in theaters. My phone was blowing up in a way that doesn’t typically happen with other movies. “let me know when you watch it!!” “what did you think!?” “I’ve already seen it three times girl, what are you doing???” I’m a born and raised Mississippian, though I live in Los Angeles now. So, it makes sense that my friends wanted a stamp of approval from a bonafide Mississippi diva.

However,

There are countless critiques, explorations, and celebrations for Sinners on the internet. As much as I thoroughly enjoyed the movie, I haven’t felt the need to participate in the conversation. I figure I’d let the girls who were discovering southern gothics for the first time do their thing. That’s no shade, baby. I’m just in a place where I don’t have to dissect everything in order to enjoy it. Even in real life, I find myself quiet during conversations about Sinners. I want to hear how it resonates with people who maybe aren’t use to the atmosphere, themes, and storytelling elements that I associate with the deep south.

But I do want to say two things: I was really touched by the use of music in Sinners. (weren’t we all?) And. One scene in particular gave me a revelation that struck me in the heart.

Thing One

Sometimes when Hollywood or even Black Hollywood™ makes a Historically Accurate Black Movie™ they score it with rap, or neo soul, or R&B etc. I largely believe this is to deliver atmosphere and storytelling context to a contemporary audience. Still, I think it corny, it’s cheesy, it’s lazy, and I don’t like it. But Sinners didn’t do that. The film opens with soft country music which immediately pulled a strong reaction out of me. Yes, this is it! This has always been our music. This is what the air feels like where I grew up! From the jump, dir. Ryan Coogler seemed to focus on grounding the supernatural in what was real about my home state. I gladly trusted him to take me on an adventure in a world that I recognized.

Thing Two

There’s a scene where Stack, Sammie, and Delta Slim drive down a gravel road when they pass by imprisoned men. Delta Slim preaches words of encouragement to the men that he once knew. His words are met with a gunshot and it instantly sends him back to a deep place of mourning. Watch this, now. Delta Slim lets out a cry. The cry becomes a hum. And what is that hum if not soul music? There’s that revelation I mentioned earlier.

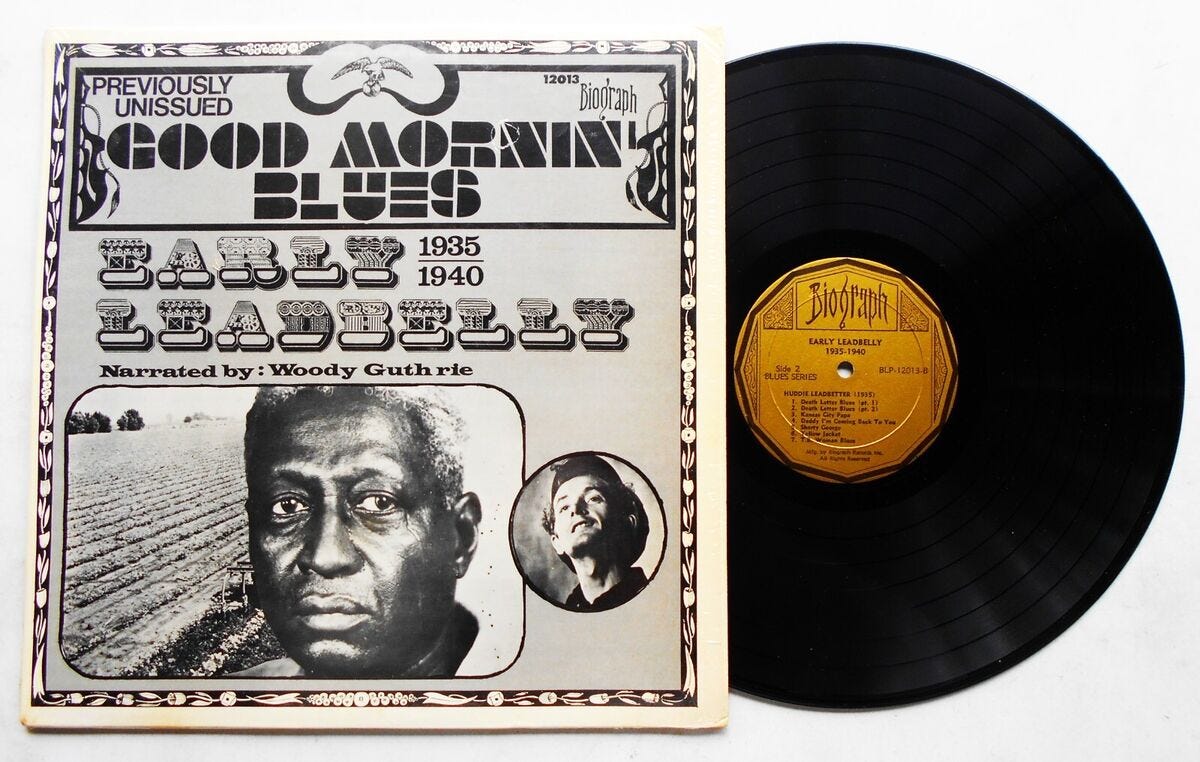

The moment actually reminded me of a blues vinyl I recently purchased at a cute little spot in Highland Park. I listen to a lot of blues and black folk music because it helps me stay present as I write and rewrite my southern gothic. (yay) It’s a pilot. (boo) Anyway. The vinyl, GOOD MORNIN’ BLUES, features songs performed by Early Leadbelly from 1935 to 1940 and a biographical narration by Woodie Guthrie. Over a sentimentally grainy sound quality, Guthrie speaks about Leadbelly, the blues and folk songs he sings, and how the songs came to be.

I find myself collecting more music like this because it connects me to home and something spiritual, maybe even supernatural. I feel proud to be in cultural ownership of this art and my soul rests easy in what is simultaneously familiar and distant.

Guthrie describes the cultural songs that Leadbelly grew up singing as “hollers.” Hollers?? Oh, hollers… Hm… Walk with me. At the turn of the 20th century, American white people’s ear for music is largely shaped by Christian hymns and classical music. That isn’t to say those were the only genres they participated in, but here’s what I’m getting at: they’re used to mixed voices, falsettos, head voices etc… they sing with a reserve. Is it accurate to say that whatever power they infuse into their voice seemed to go up, not out? Sure, there are other contrasting genres like war songs or Irish and Scottish fiddle music. Still, I think it makes sense that they’d hear these little black kids singing, maybe one or two generations removed from slavery, and say, “Why are they hollering?” It’s because black people were singing with their chest voice. Their sound was full, took up space, and expressed emotion.

So, now. (wow) I feel like I’m looking at somewhat clear evolution of soul music from the perspective of hollers. It’s fascinating to think that in the absence of the genre’s title (soul music), white people resorted to condescendingly describing the sound of black peoples’ voices or, in this case, their souls. Of course, the origins of soul music are credited to mid century Gospel and Blues. But I don’t think it’s a stretch to say that the elements of the genre date even further than that. Delta Slim grieves and cries with his soul and it’s music. Classic R&B is full of mournful wailing and crying with romance on the mind. Does that mean soul music could have been birthed through the pain and suffering of black people in America? I could see the argument.

So, shout out to Sinners for presenting an evolution of black music through an intimately human context. It’s helped me connect some dots that only deepen my love for southern black music. I, of course, could say more on Sinners, especially when it comes to music. But I won’t. You can’t make me. Instead, maybe I’ll finally finish that video essay on blues music as a nuanced reflection of mid century southern pop culture. (Now, that I’ve told you about it, I have to actually do it.)

until next time, RheAnn<3